Seeking Wisdom:

Orthodox Education and the Right Relationship of Human and Divine Wisdom According to St. Gregory Palamas

Fr. Matthew Penney, Ph.D.

Saint Kosmas Conference

California

November 2018

Thank you, everyone. I’m glad to be here with you. I’m Fr. Matthew Penney, and I have had the great blessing over the last few years to do my doctoral research on one of the greatest saints of our Church, a great saint and theologian, Saint Gregory Palamas.

What I want to do today is to try to take this great learning and the great life of Saint Gregory and try to pull out some principles for you, some guidelines, in order to think about our topic today. I am a very strong believer, strong advocate, that the theology of our church, even in the most complicated ways, is actually really, really practical, if we can make those connections and if we can understand the repercussions of these theological principles, which is why they’re so important, which is why one Greek letter, an iota, can mean the difference between Christ being God and Christ being a creature.

So, hopefully, today, I’ll be able to give you some principles from the wisdom of Saint Gregory that will help you in how you approach choosing your curricula and how you approach teaching it.

In particular, what I want you to take before we begin and keep this in the back of your mind, that for Saint Gregory education is about prioritization. All of a human life, actually, is about prioritization, and that is going to be a defining feature. How do we get our priorities in order and straight? We have heard this from many of our speakers already—regarding the disordered, the fractured nature of human beings. That’s where I want you to cast your mind. So, I’m going to jump in because if I take any more time, we’re going to be late.

So, my topic is Seeking Wisdom: Orthodox Education and the Right Relationship of Human and Divine Wisdom According to Saint Gregory Palamas.

Who is Saint Gregory Palamas, anyway? Originally, I had three slides [on the life of Saint Gregory], and I was going to tell you all these wonderful things about the life of Saint Gregory because he’s amazing. I will commend you, either to ask me some questions about him in the question period, or to go and look this up. But for the purpose of our time and getting more to Saint Gregory’s thought on education, I’m just going to give you a very brief version of his life. He was born in 1296 to an aristocratic family from Anatolia. He moved to the center of the Byzantine Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire of Constantinople, as a child, where his father was a senator in the court of the emperor Andronicos II.

To give you the paragraph version, we’re going to turn to a contemporary saint, or close to contemporary, Saint Nicholai Velimirovich, from his Prologue of Ochrid. This will just give you a snapshot of Saint Gregory’s life. Saint Gregory’s father was this eminent official at the court of emperor Andronicos. He was also the personal tutor of the grandson of the emperor, the future emperor Andronicos III. Saint Gregory, himself, was educated alongside the emperor. So, he had this tremendous education from his father, Constantine, who is also a saint. The gifted Gregory, completing his secular studies at the age of 17, did not want to enter the service of the imperial court, but withdrew to the Holy Mountain and was tonsured a monk. That is a very short version of the long and windy path he took to the Holy Mountain.

He lived a life of asceticism in the Monastery of Vatopedi and Great Lavra. He led the struggle against the heretic, Barlaam, who was an Italian monk from the West who became initially Orthodox but apostasized by the end. Their debate is central to where you are going to get this teaching of Saint Gregory on education; it’s from this controversy. This took place for at least ten years, really longer, and it was about how God is known. That it is essentially the center of conflict—the knowledge of God, and the knowledge of the world and human knowledge in light of that. We’re going to see some of that today.

Saint Gregory was consecrated Metropolitan of Thessaloniki in 1347, and glorified as an ascetic, a theologian, a hierarch, and a miracle-worker. That just gives you a bit of a sampling. It doesn’t mention Christ, who also appeared to him. The Most Holy Theotokos, Saint John the Theologian, Saint Demetrios, Saint Anthony the Great, Saint John Chrysostom, and angels of God appeared to him at different times. This is the character and the spiritual life of this great theologian of our church who grew up in the center of the worldliest of worldly places, if you think of the world of his day, in terms of political power and those kinds of things, and yet this is the kind of fruit of his life. He governed the church in Thessaloniki for 13 years; spent a year in slavery. He reposed in 1359, and his relics repose in Thessaloniki, where a beautiful church is dedicated to him.

Here you see in the middle photograph—those are the relics of Saint Gregory. I’ve had the great blessing of venerating these relics numerous times while I was living there. Here you see the church dedicated to his honor, there in Thessaloniki. So, that is by way of a quick version of his life. If you want some more details, feel free to ask.

Saint Gregory’s ‘philosophy’ of education: To answer, for Saint Gregory, what exactly were his views on education, we need to dial it back a little. That’s been something common, I think, in terms of the talks by our speakers today. We must ask some fundamental questions about education. The first, most fundamental question should be: What is the purpose of education? What is an education for? Because how we answer that question is going to radically determine the form our education will take. But this can really only be answered by asking an even more fundamental question—which Saint Gregory is clear to underline—which is: What is the purpose of human existence? So, depending on how we speak to this point, that’s radically going to be: What is an education? And what is an education for? And it is determined by this kind of principle. This is where we’re going to begin—with Saint Gregory’s answers to these two questions, and we’re going to start with the more fundamental one—the purpose of human existence.

What is the purpose of human life for Saint Gregory? Well, Saint Gregory in many places writes, “The goal before us is God’s promise of good things to come: adoption, deification [or theosis], revelation, and the possession and enjoyment of heavenly treasures.” So, that’s clear. And, again, it’s clear from the speakers that we’ve heard so far in the things that we’ve talked about. But an important reality is: How do we achieve these wonderful things? That is going to be determined by the state in which we find ourselves as human beings.

We see here in this icon of the casting out of Adam and Eve from Paradise. Saint Gregory writes for us: “Through the fall, our nature was stripped of this divine illumination and resplendence.” We find ourselves, as human beings, in need of something as part of the purpose of our human existence.

For Saint Gregory, his motivating concern in everything he's doing is for the salvation and the transformation of human beings. We've talked about that. We can talk about that as theosis. We can talk about that as the spiritual life. We can talk about it in many different ways. But, when you boil it down, what Saint Gregory is concerned with is: What contributes to the salvation of human beings and their transformation, and what doesn't, or what gets in the way? That's important to bear in mind.

Because human beings are fallen, because we are disordered and broken, we’re in need of salvation, of restoration, and of transformation. This is a disordering of our spiritual and our psychological condition. We talked again about that with the intellect versus the nous, and things like that. So, the answer to the question: What is the purpose of human existence for Saint Gregory? It is achieving one's salvation by means of personal transformation in the Body of Christ through union with God. It's not enough to have the right faith if we don't do anything with it. Saint Gregory is clear about that in other places.

What then is the purpose of education for Saint Gregory, in light of the purpose of human existence? The purpose of education is to facilitate, to contribute to, and, importantly, not to hinder human salvation and personal transformation (or theosis). It’s going to be according to this as a principle that Saint Gregory is going to assess the value of any form of education and of any curriculum.

This is a principle that we can take and apply in our own approach to the material that we teach our children. Does it facilitate? Does it contribute? Is it consistent with our faith? Does it lead us deeper in our desire to know about the universe, and to know about the God that created that universe? And does it not hinder that? If something gets in the way or distracts from that purpose, or the reality of God in the universe, that’s going to be something that Saint Gregory is going to find very problematic.

This is also the lens by which we’re going to evaluate the relationship of human wisdom and divine wisdom, which for Saint Gregory are separate things, and particularly as they’re played out in the two educational traditions of Byzantium because this is where he is from—14th century Byzantium—and the educational context that he has.

To give you a brief synopsis—this aspect is somewhat historical—but a brief synopsis of these two educational traditions of Byzantium. There were two traditions they always spoke about: the exothen tradition, which could be translated as the secular tradition or the pagan tradition, and the kath’imas tradition, which would be translated as the spiritual tradition.

The interesting thing about Byzantine education is that it’s one of the most concrete forms of continuity of pagan Rome. Remember, they didn’t call themselves Byzantines—maybe you don’t know this—They called themselves Romans. In Saint Gregory’s time, he addresses the people of Thessaloniki as: “Us, Romans” or “You, Romans.” This is just the continuation of that with the educational system.

There’s this wonderful quotation from Marcopoulis, a Byzantine scholar, who just points this out for us. He says, “The educational system in Byzantium was, in all major respects, the ancient educational system.” I think this can be striking for us in some ways that in eleven hundred years of history, they didn’t feel the need to create a specifically Christian curriculum that warred with the secular one that was in place. Rather, it was going to be about how they approached that material, how they used that material, and how they prioritized that with respect to the spiritual life.

Exothen: you’re going to hear me use that term, so try to put this in your mind. Exothen, which is secular or pagan education, literally means “education from outside.” Exothen education represented, as I said, this education of the pre-Christian, of the Greek and Roman culture, that was inherited by the Christian Romans from 330 up to 1453. If we wanted to describe it, we could call it “a program of mental formation by means of a highly standardized curriculum.” Now, when we say “highly standardized” in this way, what we mean by that is the same sorts of authors were being read in education, the same classical authors were being used—with some editions here and there of some various contemporary Byzantine people in their days—by everyone for nearly 1100 years.

Now, this is going to be shaped by what access to texts people had, what access to teachers you had, what was going on in the empire because in an 1100-year period, a lot goes on. But it’s amazing the way in which the authors that they were reading and using remained relatively stable throughout that period. They’re staples. I can talk to you about those, but I’m not going to get into that now because we won’t have time. But if you wanted to know the names of some of them, just out of curiosity, that’s a great question for the question period.

So, this curriculum consisted primarily of classical antiquities, what we would think of the trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric (all of which are language-based), and the quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy (which are number-based). Again, we could talk about particular authors that were taught under these ‘subjects,’ as it were, but we can leave that. That just gives you a bit of a picture.

The exothen education had basically three stages to it: primary, secondary, and higher education.

Primary began at approximately 6 to 8 years of age and generally lasted 3 to 4 years. This would take place by private tutors in courtyards by clergy. It was basic literacy skills (learning letters, learning combinations of sounds, vowel combinations to words, basic reading), as well as basic numeracy (learning how to count, mostly using your fingers and stones, as well as abacus counting boards). They didn't have textbooks, so what you got from your teacher is pretty much what you had.

The secondary, which was called the “Encyclios Paidea” (‘The Cycle of Education’), is more what we would think of as this kind of classical trivium and quadrivium. It began at about 12 to 16 years of age and lasted about four years, and again, with the break-down that we saw in the last slide about what those subjects were.

The final one, higher education, began after the completion of the “Encyclios Paidea” and was really a continuation of that, to be honest. You would do a lot more with rhetoric at the higher level. Rhetoric is public speaking, learning how to speak, and order your thoughts to speak publicly, and that kind of thing. But it also takes written forms. Philosophy, and then, interestingly, theology only at the highest level, if you did that.

Now, we’ll switch gears and look a little at the kath’imas education (or the spiritual education) of Byzantium. The kath’imas is literately “our education”—that’s what it translates to be. So, we have the education of those on the outside, and we have the “our education.” Specifically, for someone like Saint Gregory, a Byzantine author of his day, the “our” refers to Orthodox Christians. This is the context in which this “our,” the kath’imas, has any context, or any meaning. Saint Gregory will go even so far in one place to refer to it as “Holy Spirit education,” and he contrasts that to the education of the Egyptians and the Greeks and various others.

In its basic form—if the other is a program of mental formation—we would say the kath’imas education is a program of spiritual formation by means of some theoretical knowledge (like we might think of catechetical instruction, basic theological literacy), but primarily this is an education through action on the basis of this knowledge. It’s about what you do with it. So, what does that really mean? It means we’re talking about knowledge gained through experience in the practice of the Christian life. That’s what the kath’imas education was.

What did this kind of action look like? What do we mean when we say the spiritual life?

Well, in particular, at its basic level, we are talking about the following of the commandments of Christ and the acquisition of virtues in cooperation with the Holy Spirit. I had a wonderful introduction with Dr. Mark Tarpley's paper, and I appreciated that very much. This acquisition of the virtues in cooperation with the Holy Spirit—that's what gives real meaning to this.

It also involved a life of prayer, participation in the Mysteries of the Orthodox Church, of which we've said much. But, at its deeper level, this form of education, to speak of it this way, is seeking an experience of communion with this transcendent yet personal Trinitarian God.

In particular, at its most developed we're thinking of this term here, “theoptia,” which Saint Gregory uses a ton. Theoptia being Divine Vision or Vision of God. It's what we would think of as the Vision of God in the Uncreated Light, things like that. This is essential on your road toward theosis, toward this personal transformation and perfection. It's an experience of communion.

Now, the experience is not something we can plan for. It's a gift from God, if God chooses to give it. We can make ourselves open to being able to receive it. How? By doing these other basic things, by living our faith. But the fruit of this—and this is what's important for Saint Gregory—is this notion of human transformation and this movement towards personal purity and personal perfection, in Christ, of course.

The second one applies particularly to this deeper level, which is a direct transmission of knowledge of God, of knowledge of divine things in a way that is certain, because it's given by a Giver who is capable of transmitting that knowledge in a way that we don't mess it up. That's the wonderful thing—when God speaks to saints, it's pretty clear that He's speaking to them, and it's very clear what He's saying. Whether Moses wanted it or not, it was clear that God was speaking to him, and this is the same with the experience of the saints.

The other aspect of the kath’imas education is this: If you’re saying, “Okay, Fr. Matthew, you said there’s an exothen curriculum—give me the books before I leave—and then we have this kath’imas education. Can you write me a list of those spiritual books too so that my kids can be purified, deified people, and become saints who experience the revelation of God?” It doesn’t really work like that.

There really isn’t a fixed curriculum, per se, when we’re speaking about the kath’imas education, because we’re actually not talking about religious education classes. This is oftentimes what we think of when we’re thinking of this kath’imas education. We’re thinking, “Well, as long as I send my kids to Sunday school, or send my kids to catechism class, or we have an hour set aside in our day or in our week for learning about the faith, then I’ve somehow fulfilled the spiritual responsibility of teaching my children.” That’s just the tip of the iceberg.

[Religious education classes] never really existed within Byzantium, except maybe in some monastic schools you’d get that, but even in the monastic schools oftentimes you’re still getting the other kind of education which could prepare you, as it were, and then you’d get this religious or theological education at the highest levels because you were going to be teaching in the patriarchal schools or that kind of thing.

It’s important to understand that the kath’imas education is not determined by the curriculum, but rather is determined by the end result. That’s what was important with the kath’imas education. And this end result was union with God and human salvation above and beyond any single kind of curriculum.

The reason why this is important for you is because this is the area where you have the most flexibility, we might say. This is the area where how you practice the spiritual life with your children in your context is going to be vitally important.

This is the area where you’re going to be involving your spiritual guides. And the spiritual guide for your family may have a path that’s different than the spiritual guide for this family. Or even the same spiritual guide for two different families [may have a different path for each] because that’s based, again, on trying to achieve a certain end result. So, the path to achieving that can be slightly different depending on the context of your family and the spiritual guidance for your situation. That’s an important element of this.

So, again, why don’t we have a fixed curriculum in the kath’imas? Why is it so hard to find what they were reading or teaching the children? Well, mostly because the goal [of the kath’imas education] was this higher goal, and it was a very experiential character. “Put it into practice and learn from that” — that’s the greatest education.

Are we saying that there was no formal kath’imas education? Where did it take place? Why did the Byzantines write so much about it? Why do the Fathers speak about this kath’imas education so much then if we don’t have it in the schools?

Well, it was taking place in the Church, and it was taking place in the home. A great place to look at that is in the writing of Saint John Chrysostom. Fr. Josiah Trenham has a book, Marriage and Virginity According to St. John Chrysostom. In that book he walks you through some of this stuff: the way in which what took place in the Church was meant to be translated into the home, and that the family was meant to take what they had learned in the Church and continue to discuss it, continue to develop it, in the home.

Where was this kath’imas education taking place? It was taking place in the whole culture. The entire mindset of this entire culture was based on the foundation of Orthodoxy. It was a part of their government; it was a part of their daily life with their church experience.

We see, in particular, they’re being taught the faith in these tremendous homilies that were being preached. We think of the homilies of Saint John Chrysostom. He would preach homilies that would be hours in length, and people were asking him to continue preaching. People were getting riotous over it, and he had to calm them down and reel them in. This was the zeal with which they were teaching and learning. So, we have that as one of these forms.

We have these huge collections of teaching letters, scriptural exegesis, theological explanation. The Byzantines loved letter-writing. You want to talk about forms of writing—letters were big for them.

We also see that this kath’imas education—the theoretical side of it as well as the practical—was taking place in things like the development of the Church calendar, of the feasts and the fasts. If you are practicing and aware of the feasts and the fasts of the Church, and the Church calendar, you are absorbing so much of our faith, just by paying attention to that, just by going to church during those days.

We also have the development of hymnology taking place. We have hymns that are being written to interpret Scripture for us, to interpret the faith for us. These were all sources where people—even if they weren’t formally sitting in a religious education classroom—were absorbing a lot more, in many cases, than even we have the opportunity to do.

We have the same with the confirmation of the icons, with the development of liturgical symbolism. What were the icons? “Theology in color,” “The Bible for the illiterate.” All of that emphasizes this place of contact where people were learning their faith in practice. Think of our little children. How do they learn to relate to an icon? They relate to the icon truer than any of us, especially us converts, because they do it just naturally. In the same way they would run to hug any of us, they run and they hug the icon, and they’re kissing it, doing all these lovely things. They relate to the icon in a way that’s actually natural, and the theology, [the child’s] theoretical knowledge, develops with that as they grow.

We also have these amazing collections of theological quotifications; Saint John of Damascus is one in particular.

These were all ways that the kath’imas education, the theoretical side, was being transmitted. But that’s really not the most important aspect of that, and that’s not so much what I want you to take from it. The spiritual education is the practice of our faith in action, informed yes, by the knowledge of our faith. But, again, if we don’t do anything with it, it doesn’t mean very much.

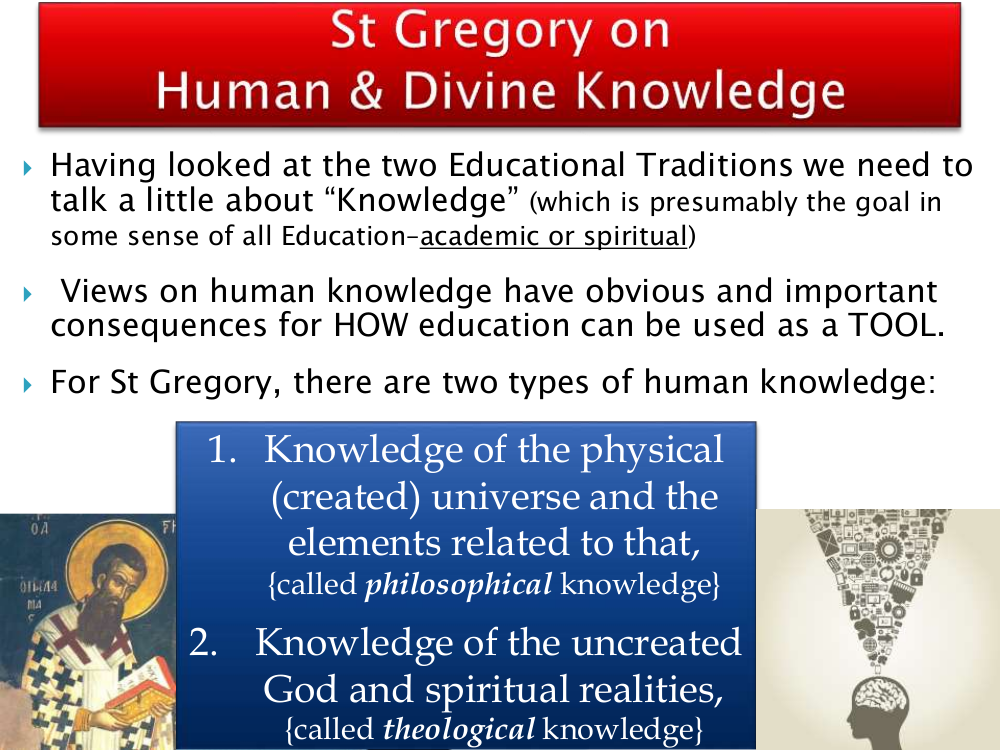

So, let’s shift gears a little. That was your historical introduction for the day. Now we’re going to jump a little bit more into Saint Gregory on Human and Divine Knowledge. Having looked at the two educational traditions, I want us to talk about the idea of knowledge because, as I said to you in the beginning, this is very important for Saint Gregory. This is very important in the context of this debate. Presumably the goal, in some sense, of all education, is some form of knowledge, whether it’s knowledge of the living God through experience, or whether it’s some form of theoretical knowledge about the way the world works, and that kind of thing.

Saint Gregory’s views on human knowledge are going to have obvious and important consequences for how education can be used as a tool. Because, as I have already said to you, for Saint Gregory, education is for something; it’s for a purpose. It has to facilitate and contribute to and not get in the way of the purpose of human existence. So, understanding how knowledge works, will be part of how we see and how we can use this as a tool that will be for the building up and will be profitable for us.

Saint Gregory says there are two types of human knowledge. Just take a second and think about that. There are two types of human knowledge. The first type is what we would normally think of as knowledge, especially when we’re talking education—knowledge of the physical created universe and any of the elements related to it. We can call that philosophic knowledge. We can call it scientific knowledge. We can call it academic knowledge. It’s that knowledge that aims to talk about and explain the physical universe—however small, however big. That’s the domain of this kind of knowledge.

Then there’s a second knowledge that Saint Gregory will hold out for us, and this is knowledge of the Uncreated God and spiritual realities. We can sometimes talk about this as theological knowledge, though Saint Gregory will even distinguish it from theology, amazingly, and say it’s even more profound than that, in terms of this kind of knowledge.

We’re going to see that Saint Gregory uses this term: two types of “knowledge” and, in particular, two “wisdoms.” From this notion of two wisdoms, you can guess which form of education is going to deal with the human knowledge, and which form of education is going to deal with the divine knowledge. You probably already have a guess—The exothen and the kath’imas, for the human and for the divine.

Saint Gregory speaks to us about it. He says, “Indeed, to be introduced of one’s own accord into the knowledge of beings, the exo philosphy [or this exothen education] is perhaps not entirely false, under the condition of course that the knowledge is accurate. But this is not the knowledge of beings and wisdom which God has directly given to the prophets and the apostles.” Why is this important? There are two types of knowledge here. Why is this important? Because in Saint Gregory’s day, he had people who were saying that if you didn’t study the exo philosophy you were a second-class Christian, more or less. You weren’t necessarily going to become holy, and possibly you couldn’t even be saved. Now, maybe you didn’t go quite that far, but those are certainly the repercussions of it, I think.

Saint Gregory wants to be clear to distinguish this because—if we have a purpose with our human life and we only have so much time to exercise in that purpose—we want to do things in the most effective way to facilitate, to contribute to, and not to hinder. What Saint Gregory was noticing is there was a hindrance happening because exothen philosophy was being given too much of a place, too much of a role.

This is a quotation by a scholar on Saint Gregory who points it out, just to make it clear: “Saint Gregory emphatically points out that there are two wisdoms, the one seeking to satisfy the needs of social life and intellectual inquiry, and the other leading to salvation. The distinction is obvious from the existence of the double gifts of God; some are natural and are given to all, but others are spiritual and supernatural, given only to the pure and the holy.”

That speaks to how that knowledge is acquired. Anyone can acquire scientific knowledge by opening a book or by opening their eyes and looking out on the world. But this other form of knowledge requires an experience of the Living God in a very direct kind of way, in a very experiential kind of way, built on the foundation of Christ, and that’s where this second form of knowledge comes from, that leads to salvation.

I’ll underline this because Saint Gregory will go to great lengths to make this point—that the truth of the Greek philosophers is NOT the Truth of those “philosophizing according to Christ.” This is the phrase he uses. That’s not to say they’re in contradiction—Saint Gregory is not going to go that far—and you’ll see that as we go along in the talk. How do these things then fit together? He had an exothen education himself. Exothen education is not the problem. The problem is the misuse of it, as we’ll see.

His point is to say: Do not become confused to think that the truth arrived at by the Greek philosophers is somehow the same as experiencing the mystery of the Holy Trinity, or the same as experiencing communion in the Body of Christ. They may look similar, they may be consistent, but they’re definitely not the same. It’s the difference between talking about peace in the world or being peaceful, versus the peace of Christ. One is an uncreated peace; it is an experience of the Living God in a way that’s different from, even if similar to, what we would normally mean by that word [peace]. That’s just an example.

Saint Gregory’s problem with them, with the situation, is that, “They speak as if there’s only one kind of knowledge, and claim that this constitutes the aim of contemplation,” i.e., they’re saying there’s only one kind of knowledge, one kind of study that matters, and it’s the same whether you’re studying secular philosophy (secular studies), or your aim of contemplation, your knowledge of God, your kath’imas education. And Saint Gregory is saying: No, no, no! That’s a confusion of the boundaries and the aims of these educations.

Here is what actually happens. Saint Gregory says, “And here is a fact which will reveal to you something of the terrible depth of evil into which the worldly philosophers have fallen.” I mean—wow!—strong language, right? “The terrible depth of evil.” Why is this so terrible? Why is this so evil, what they’ve fallen into? Because what they’ve fallen into is taking the path to salvation and taking education that should contribute to [salvation], and they’ve put it firmly in front of that as a hindrance. So, rather than leading you up to God, they’re leading you over here, somewhere else altogether, and that’s the great evil he is speaking about. How conscious they were of it or not, it really doesn’t matter for Saint Gregory. The end result is the same—people get ruined, and that’s a terrible thing.

Saint Gregory wants, again, to underline this distinction for us: “Is not the truth of this wisdom of divine words necessary, profitable, and saving to us, while that related to the exothen is neither necessary nor saving.” He’s not saying it’s evil. He’s not saying it’s bad. He’s not saying we won’t use it. But he’s just making the point: it’s not necessary, and it’s not saving. If you have to choose between learning to pray and learning to read, then learn to pray. It was the same as Andrew said: If you must choose between learning to write and learning to pray, it should be a no-brainer. But those aren’t in opposition unless we make them in opposition. But one does lead to salvation, and the other by itself will never lead to salvation. That’s important.

Saint Gregory says, “From which it is shown that the form of truth is double, of which the end of one is God-inspired teaching, while the other neither necessary nor saving; the exo philosophy seeks but falls short.” He’s particularly critical of when exo philosophy wants to talk about, for example, the Nature of God, the existence of the soul, and different things like that. He says what we would say: That’s beyond the scope of science to talk about. Science deals with the physical universe. What do contemporary academics, philosophers, and scientists have to say about whether God exists? That’s not part of their field of study. They study the physical universe. God is part of the invisible, the uncreated universe. Science can’t touch that area. That’s what he’s pointing out here.

Saint Gregory says, “How then do we find one truth by means of both of these?” His point here is: We don’t. One can contribute to the other, but we cannot confuse them and say they are two equal paths both of which lead to God, or say that all roads lead to Truth, or something like that. If it’s consistent with revealed Truth, then yes, and scientific knowledge of the universe that we can confirm by study, yes. But, Saint Gregory’s point here is: Our faith is a revelation.

The Holy Trinity is not something that by human speculation we could have arrived at. Yes, there are images of that in nature and even within the human person, so that a person could come close to that. But, the full revelation of the Holy Trinity is not possible [by contemplation]. Because why? The Scriptures tell us we needed our Lord Jesus Christ, the God-man, to come down and reveal the Father. That’s why the Scriptures say: Without the Son you can’t have the Father, precisely because that’s what the Son does—He reveals the revelation of the Incarnation of the Holy Trinity. He reveals how it’s possible for the Body of Christ to be both His Church and His Flesh, something that we eat to be transformed by. This is a great mystery that the human instinct can’t penetrate. He’s saying there are two kinds of knowledge here, and to bear that in mind.

So, does he reject all these things? You may say, “Well, Fr. Matthew, those quotations you presented were pretty harsh. Does Saint Gregory hate philosophical, scientific, psychological, social, political, and all of this kind of knowledge?” No. He doesn’t have a problem with it, and as we’ll go on to see, he actually thinks it’s useful and beneficial when it’s contributing to human salvation and personal transformation. But when it gets in the way, he’s not going to pull his punches. He’s going to call a spade a spade, as it were, and just deal with it.

Saint Gregory does not reject philosophic knowledge from exothen studies, but he wants to keep it within its proper limit, within its proper domain, within its proper area of specialty, which is facilitating human salvation and transformation, but never getting in the way of it. Here’s a quotation where he says this very clearly: “If someone says that philosophy, in the sense that it is natural, is a gift from God, then they speak the truth, without contradicting us.” His issue isn’t with the use of the intellect to discover truth.

What determines, for Saint Gregory, whether philosophy or science is good or bad is how it’s used. Again, does it facilitate?, or does it get in the way? He gives us this lovely quotation, and you’ll get a little picture of this Byzantine education we’re talking about. Saint Gregory says,

This knowledge too [of celestial spheres, moving and symmetrical, and their properties] is both good and evil; it is good in its nature, but the intention of those who use it modifies it in one direction or another. More importantly, I will say here that the practice of the graces of the different languages, the power of rhetoric, historical knowledge, the discovery of the mysteries of nature, the different methods of practicing logic, the different viewpoints of mathematical science, the varied forms and measures of immaterial science, all these things are at different times both good and evil. This is not only because the way they appear is a result of the thoughts of those who use them so that they easily take a form shaped by the point of view of those who possess them. It is also because studying them is a good thing, but only to the measure that through it they develop sharpness of vision in the eye of the [soul].

The exothen education, this kind of secular education, the skills that we’re teaching our children—I don’t know if “secular” is the right word, but this kind of education that we’re giving them—if it contributes to their spiritual life, if it helps them to be more discerning, to understand their faith better, to learn practical wisdom to practice that faith better, then it’s going to be very good.

This is a bit of a side note, but it’s very important for us too. This is not only because the way they appear is the result of the thoughts of those who use them, so they take the form shaped by the point of view of those who possess them. What he’s pointing out here is: Depending on the worldview and the mindset you have, that is oftentimes going to affect how you read data and how you interpret facts. We can think of many issues in our contemporary world, whether it’s about evolution versus creation, the nature of the universe, human sexuality, gender, and all of these things. There are now a lot of academics and scientists, professionals in universities, who are standing up and saying, “No, no, no, listen. Here are the facts that prove exactly what I’m saying.” Saint Gregory is pointing out even in the 14th century, the problem with this kind of knowledge is that you can view the facts in light of the mindset and the paradigm that you already accept, and so you’re seeing the conclusions that you already have arrived at in your mind, and it’s just reinforcing that.

His point here—not to get off into all of that—is just to say that study itself is neutral. It’s how we use it that will determine whether it’s good for us and for our children, and whether ultimately it contributes to or undermines our salvation. In this case, the ends and the uses of our secular education play a definitive role in assessing the good or the ill of this type of knowledge.

How do we sum up his views on human and divine knowledge? Basically, the essential difference between the exothen and the kath’imas educational traditions is that one pursues knowledge chiefly by the use of the intellect. It’s not good or bad; it’s just the methodology by which it arrives at these conclusions. The other seeks an experiential knowledge of God by means of the human nous and union with the Holy Spirit. If we try to pursue one or the other using these wrong methodologies, we end up having the wrong conclusions. We end up in these dead ends.

These are two lovely quotations. We probably only have time for a little, but I’ll read it anyway. Here is St. Gregory saying that this vision of God, this kath’imas education, is even different from theology. He says, “Theology is also far removed from the Vision of God, Divine Vision, theoptia, the Divine Vision in Light. It is as different from intimate conversation with God, as knowing something is different from possessing it.” And this is the line I want you to take home with you. This is what you need to remember from this talk—other than ‘prioritization’ and ‘contributing to and not hindering’—you need to remember this line by Saint Gregory: “To say something about God is not the same thing as meeting Him.” That represents the fundamental difference between these two paths of wisdom. They’re not the same thing, and if we don’t have a meeting with God, then we don’t know Christ. And I don’t mean you have to have visions of the Divine Light or any of that. That’s not what we’re talking about here. But the experience of the Living God in our Lord Jesus Christ—this is what we’re aiming for.

Perhaps you’ll say, “Well, this is kind of vague, Fr. Matthew. I don’t understand this knowledge. What do you mean by Divine Vision and all this? What does this mean?” Well, Saint Gregory unpacks that a little bit for us. He says, “Do you now see that in the place of the nous and eyes and ears, they (the saints) acquire the incomprehensible Spirit. It is through Him that they see and hear and understand, so it is not the product of either imagination or of discursive reason; neither is it an opinion nor conclusion reached by syllogistic argument.” This is the difference.

Here is an example, but it doesn’t exactly fit it. Before I came here, you could have read my biography on the website for this conference, and you got a whole bunch of facts about me. You learned lots of different knowledge, you used your discursive reasoning, and maybe you formed some opinions about me based on different things. But when I walked in the room here, and you saw me standing here, you immediately gained tenfold the amount of knowledge about me just from seeing me. And especially from the moment I opened my mouth, and you started to hear me talk and express, there’s an intuitive knowledge that you gained about me, just by experiencing me. This is the sort of distinction that Saint Gregory is driving at with this.

What’s important is that this knowledge that comes from God—It’s not an opinion. It’s not something that the saints can be confused about because it’s not discursive. It’s not about imagination. God gives it directly, and that’s really important. That’s why we always talk in the Orthodox Church about following the Holy Fathers, being consistent with the Holy Tradition. Why? Because we believe it’s a revelation, not philosophic speculation. So, that’s the theological point on that.

What should the balance be? In dealing with this question, Saint Gregory, as we’ve said, speaks with these two types of knowledge and these two types of educational traditions that go with them. But he makes this threefold division. He’ll talk about the philosophy of Christ or philosophizing according to Christ, and this is what is meant basically by this kath’imas education. He talks about vain philosophy and natural philosophy, and essentially, they’re the same thing. They’re both exothen; they’re both scientific knowledge, academic knowledge, or knowledge of the universe. The difference [between vain and natural philosophy] is that one is used to contribute to human salvation, to the kath’imas, and the other one becomes an end in and of itself and shipwrecks our salvation. It gets in the way. It becomes vain; it becomes useless. Think of the word vain. And Saint Gregory will draw that distinction. I give you a few of his teachings on this.

Saint Gregory says, “Certain people scoff at the aim recommended to Christians. As they only know speculative science, they wish to introduce that into the Church of those who practice the philosophy of Christ. They say that those who did not possess scientific knowledge are ignorant and imperfect beings.” Take that last quotation, put it in the New York Times, and apply it to all of us foolish people here today. This is the same kind of thing that we are accused of today. By being Christians alone, people will assume certain things about you.

I’m doing my Ph.D. in a secular university. This is how I go to school [dressed in a cassock and wearing a cross], and this is who I am. And I had this wonderful compliment by a lady who was studying with me. At one point, she said, halfway through a semester, in front of the whole class, “Oh, Fr. Matthew, you’re nothing like what I expected. You’re so open-minded. You listen to other people. You express yourself.” I smiled and said, “Oh, thank you,” and in my head, I thought, “So, what did you think of me before?” With no knowledge of who I was—except that I wear a big cross; I’m one of those people, one of those ignorant and imperfect beings and what was I doing in there?—it didn’t make any sense to her until we got to dispel the fog by just being normal people. So, this applies even to us today. The words of Saint Gregory are timeless 700 years later.

When I spoke of the purity that brings salvation, I did not simply mean separating from worldly ignorance. This isn’t the primary goal of our education, to separate from worldly ignorance. It’s important, but I know, in fact, there is a blameless ignorance. This is the ignorance of Saint John the Baptist. This is the ignorance of Saint Anthony the Great. This is the ignorance of Elder Joseph the Hesychast and the Desert Fathers, an ignorance that is blameless, and [with it] a knowledge that can be criticized. So, it is not that kind of [blameless] ignorance which must be stripped away, but rather the ignorance of God and divine doctrines. This is the ignorance that our theologians have forbidden.

Saint Gregory’s point here is if you had to choose only between one form of education—which Saint Gregory is not asking you to choose—but if you had to choose, the spiritual education of your children would be the one you would choose. [Spiritual ignorance] is the one that’s forbidden, because that’s the one that teaches us about our Lord Jesus Christ, that allows us to encounter him. If you conform to the rules prescribed by our theologians and make your whole way of life better—if you put it into practice—you’ll become filled with the wisdom of God, and in this way, you will become truly an image and likeness of God.

I won’t read all of this quote because it’s a longer one, but “if we want to keep our divine image and our knowledge of the Truth intact, what do we have to do? Study more? Spend more time with books? Not necessarily. Maybe, if we need to learn patience, if we need to learn perseverance. These are tools to use in spiritual ways. But, no, primarily, we must abstain from sin. We must know the law and the commandments, not merely in theory, but by practicing them, and we must persevere in all the virtues, and in this way turn back towards God through prayer and true contemplation.”

This is a wonderful quotation right here: “Without purity, one would not be any less mad, nor any the wiser, even by studying natural philosophy from Adam to the end.” So, you could know all the knowledge, all the science, all of those kinds of things, and you’re not going to better off. Yet, even if you do not know this natural philosophy (the sciences), but if you purify and strip away the bad habits and the evil doctrines from your soul, you’ll gain the wisdom of God which has overcome the world. This is very encouraging, right? Again, it’s not an ‘either/or.’ But we shouldn’t feel ashamed; we shouldn’t feel that we’re somehow ignorant people because we want to talk about homeschooling our children and have a hand in their education. That doesn’t make us ignorant people because we believe in God.

“Do you not see that knowledge alone achieves nothing, and why speak only of knowledge of what we should do, or of knowledge of the visible world or of the invisible?” This is really important.

“Even a knowledge of God who created all things will not achieve anything on its own.” What?! You mean I’ve heard the Gospel; I’ve studied the Holy Scriptures for all these years; I’ve done (whatever). No! Even a knowledge of God who created all this world will not achieve anything on its own. What will we gain from the divine doctrine if we do not live a life pleasing to God? If we know all of these things, as Orthodox Christians especially, and we don’t actually go and become transformed—this is actually going to work against us! God’s going to say, “What? I gave you all of these tools.”

We know of the person whose house was flooding, and they’re waiting. “Oh, no, no, God’s going to save me!” And the boat comes along, and the next comes along. “No, no.” The airplane comes along. “God’s going to save me.” And eventually, the person dies, and before the pearly gates or whatever, he says, “God, I had faith in you. Why didn’t you save me?” And God says, “Well, I sent you this person; I sent you that person; I sent you that.” God gives us these things for us to use them for our salvation.

The point is that worldly education serves natural knowledge. It’s not a bad thing if we use it to the Glory of God and for our transformation.

What is a bad thing is when we fall into this: “A man addicted to the love of vain philosophy of knowledge of whatever wrapped up in it’s figures and its theories never sees even the beginning of this education in true knowledge.” How many people out there exist, and they spend their whole life studying? ... cheesecake and Jane Austin novels, I think, was one of the professors I had. It’s okay; it’s a beautiful thing and I’m not trying to impugn that person at all. We need to study the minutia as well as all of the Glory of God. I’m not saying that. But again, if we never go beyond that, what is that going to say? It’s the same for me. I read a lot of theology. If I never go beyond it and never actually do something, it’s all for nothing.

“To them who undertake Greek studies not only…” This is something from the Synodikon of Orthodoxy written about 300 or 400 years before Saint Gregory. Saint Gregory is in the tradition of saying, “Be careful how you use your education because it can get in the way.” And so in this great document of the Orthodox Church—very powerful document that we use on the Sunday of Orthodoxy—this was added to it in 1082 which said, “To them who undertake Greek studies not only for the purposes of education, but also follow after their vain opinions and are so thoroughly convinced of their truth and validity that they shamelessly introduce them and teach them to others sometimes secretly, sometimes openly: Anathema!” So, it’s fairly harsh, but what is he referring to, or what is the Synodikon referring to? Well, here are some of the teachings: “To them who prefer the foolish so-called wisdom of secular philosophers and follow its proponents and who accept the transmigration of human souls [reincarnation] and who thus deny the Resurrection, judgment, and the final recompense for the deeds committed during life: Anathema!”

Now we might be tempted to say, “Well, I’m not really going to be tempted to fall into believing in transmigration of souls or of the eternity of the universe or that there’s a world soul or something like that, like these Greeks were teaching and falling into.” Right? But might we not, through the influence of the ‘wisdom’ of secular philosophers, might we not question the existence of God? Might we not, by the wisdom of secular philosophers, question whether we truly have a human soul, whether we’re more than hard-wired machines and don’t have free will? Would we be tempted by such secular philosophers—or scientific wisdom—to question whether or not there’s life after biological death? So, these are still real temptations by education. Right? They’re different from the ones that existed in 1082 but it’s the same kind of thing.

So, what’s being laid out here for us is: Use them, but just be careful. Use them, but be discerning. And this comes down to how you choose the material that you’re going to teach your children. There’s a lot of leeway if you take the Byzantines as a model. There’s a lot of leeway, but you better—all of us better—be pretty clear that we have all of these proper presuppositions in place, that we have all of this spiritual life in place, that we have all of the things that the Byzantines had in their culture in place that we don’t actually have today. So, we must be even more careful than the Byzantines were because we don’t have all of the aids that they had.

Saint Gregory doesn’t forbid study, but he says, “We absolutely forbid those who study to expect any accurate knowledge of divine things.” So, when science wants to talk about whether God exists or not, Saint Gregory’s going to say: Foul! You can’t talk about that! That’s beyond your expertise to talk about that. When you want to talk about these kinds of questions: Do we have a soul? Do we have free will? To those kinds of questions, Saint Gregory’s going to say: Science can’t address those questions. It can speak to it in roundabout ways; it doesn’t mean it’s inconsistent with our knowledge of these things, but it can’t speak conclusively on it since it’s not possible in any way to extract any teaching about God from such an education. So this is the kind of vain [philosophy]. What does he mean: vain philosophy? Vain education is abandoning the end appropriate to simple human wisdom.

When we study this physical universe and all of the wonderful things and all the aspects to be able to express ourselves and to communicate and all of that, that’s fine. That’s fine for Saint Gregory. The issue is when we think that science—scientism, I think father called it—when we make science a god, when we make science the solution of all kinds of problems. He says it’s actually this Hellenic heresy that concentrates all its enthusiasm and interest on those who research the science of such things. Indeed, all the stoics define this science as the aim of contemplation— again, this kind of confusion of the two educational traditions. But we know of this kind of thing, so we have to be careful of it ourselves, not to become enthusiastic with our pursuit of education that we lose sight of the spiritual well-being of ourselves and of our children.

How then can we use it properly? “If someone was to say that philosophy, in the sense that it is natural, is a gift from God, then they speak the truth without contradicting us.” Just as we said, Saint Gregory is okay with that. He says, “If you put to good use that part of exothen wisdom which has been clearly separated from the rest, no harm can result, for now by its nature it will have become an instrument for good.” Right? So, there’s a great power here.

For the sake of time I’m not going to read this to you. I’ll just tell you basically [what it says]. We know of the example of Saint Basil with the bee, in his letter to the youth. “Be the bee.” We all know of that podcast series. Well, Saint Gregory has another example. He talks about the serpent and the snake and that we have to be very careful. He says that we have to cut the head off of secular wisdom which is wrong ideas about God and about spiritual realities. Right? We’ve already talked about “cut the head off, cut the tail off”. But what’s the tail? The tail is wrong conclusions about the universe based on your wrong conclusions about God. If you presuppose that God doesn’t exist and that everything is just random, and they’re just here for a certain amount of time, that’s going to affect how you view how the world works. Right? That’s going to affect your conclusions about how you look at yourself as a human being even. So, that’s what’s going on in this example.

But, when it all works together well, when exothen education is contributing to our kath’imas education, and leading us deeper in our knowledge of the universe, which allows us to appreciate God, what ends up happening is it naturally impels our soul to understand God’s creatures and then it will be filled with admiration, will deepen its understanding, and will continually glorify the Creator. This is ultimately what we want from our education, right? This is what we want for our children, that it helps to reinforce their spiritual lives. So Saint Gregory laments the Greek philosophers as we’ve said and again it’s just the restating of this. When we lose site of what education is for, when we lose site of what the purpose of human life is—which is salvation and personal transformation or theosis in our Lord Jesus Christ, in the body of Christ—then this is where we get the name in the appellation of ‘folly’ attached to it.

So natural philosophy though when it’s united properly in its right order to facilitate, becomes different from what it was: new and deiform, pure and peaceful and tolerant, persuasive, full of words which sustain those who listen to them and full of all good fruit. So we went from those very harsh comments about secular wisdom at the beginning to say that when we put education and our priorities in the right order—know the purpose of our human life: salvation in Christ—and use our education to facilitate that, then that kind of education becomes these amazing things new and deiform and pure and peaceful and tolerant, full of words which sustain those who listen to them. Right? This is quite exalted from where we begin at the beginning. This is the possibility of what you have as educators.

We have some cautionary words, but I don’t think we have time unless you really want to fight me for them. So, I think we will definitely halt it there. If you want to know what the cautionary words were—we’ve heard some already—we can talk about it in the question period. But the main thing is, my dear ones, to underline for you: the difference between this human knowledge and this divine knowledge, this knowledge that we gain from living at our Christian life and the way in which that can be transformative and the way in which what we’re doing here can contribute to that as long as we’re mindful of our spiritual priorities. So, we want to spend at least as much time thinking about the spiritual strategies for our family, as we do in planning our lesson plans for the week and that sort of thing. May God bless you. May God help you in this task. Through the prayers of our holy fathers, and Saint Gregory in particular, Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy on us, and save us. Amen.